30 years ago, the season which welcomed English teams back into European competition, Arsenal won the First Division.

Before the revolution swept away the Tuesday Club, swapping drinking for thinking and some va-va-voom, the Arsenal won their second First Division title while Nick Hornby was finishing the draft of his memoir Fever Pitch. ‘Liverpool collapsed ignominiously and we were allowed to run away with it,’ he writes, ‘despite almost comical antagonism and adversity.’

In 1991, at least, Arsenal were not ‘a Nottingham Forest or a West Ham or even a Liverpool, a team that inspires affection or admiration in other football fans; we share our pleasures with nobody but ourselves.’ Perhaps that is why nobody talks about the 1990/91 title winners. Arsene Wenger made Arsenal, to misquote him, ‘the prettiest wife’, a delight to everybody in the way that George Graham couldn’t manage to convert neutrals to.

I would like to celebrate the unloved Arsenal, ‘boring’ Arsenal, the pre-Premier League Arsenal. Nobody talks about that side because in 1989 they did the same thing in a more exciting manner. In 1998 the Wenger Revolution brought the club two trophies within a few weeks. Six years later came the W26 D12 L0 season.

But 1990/91? Those few months are probably legendary only on the North Bank terraces, one of the dates around the middle of the Emirates stand, just after the 1988/89 season and before the cup double of 1992/93.

George Graham was the manager who once again set his team to victory. History decried it for being ‘boring’ but it wasn’t actually until October when a league game finished ‘one-nil to the Arsenal’ thanks to a win over Manchester United. The goal was scored by Anders Limpar, the only non-Englishman in the starting line-up on a day which became known as the Battle of Old Trafford.

Nigel Winterburn’s naughty tackle on Denis Irwin, followed by some kicks by Brian McClair, led to a brawl which involved every player except David ‘Safe Hands’ Seaman, who had replaced John Lukic in goal as Arsenal’s number one, and Paul Merson, who ‘didn’t fancy’ a punch-up with Steve Bruce. Tony Adams writes in his memoir Addicted that the brawl ‘was really nothing…You see worse incidents over on Hackney Marshes.’ Points were docked but no pizza was thrown.

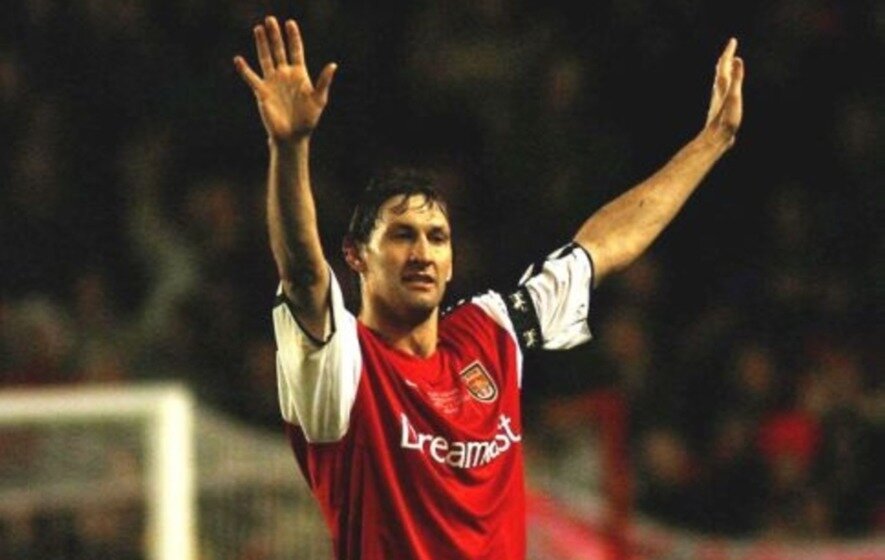

The Arsenal midfield that day contained three black players: Paul Davis, Michael Thomas and David ‘Rocky’ Rocastle (who died in March 2001 from cancer). Perry Groves came on as a substitute at Old Trafford, one of many cameo appearances. Upfront Paul Merson partnered Alan Smith, who ended the season with 27 goals in all competitions, 22 of which were scored in the First Division. Five of those goals came between Boxing Day and New Year’s Day, including in a 1-0 win over Manchester City on the first day of 1991.

An English front two now seems quaint at the top level, but ‘Merse and Smudge’ (M&S? S&M?) had the telepathy of the greatest partnerships. Indeed, a front two of any nationality seems quaint in an era of 4-3-3 and the non-number nine. Yet 4-4-2 was how George Graham had played, and thus how he managed.

Smith scored a consolation goal in Arsenal’s only league loss, at Stamford Bridge in February. On that day, the Gunners defence conceded two of the 18 goals they let in all season. In his memoir Paul Merson says in mitigation: ‘We were knackered with injuries that day and our defence was down to the bare bones.’ It also didn’t help that Steve Bould picked up an injury and young David Hillier came on to partner Michael Thomas for the second half. At least Jurgen Klopp can empathise.

No longer equipped with a mean defence, Liverpool conceded 40 goals in the league and lost ground on the champions when Chelsea beat them 4-2 and Nottingham Forest won 2-1. They also had a fun game against Leeds, going 4-0 up after half an hour before being pegged back to 4-2 and then 5-4. Because of stadium modifications, only 37,000 fans saw the 1-0 defeat to Arsenal where a Paul Merson goal moved the Gunners level on points in Tony Adams’ first game back after his prison term. Michael Thomas would move to Merseyside in November, just after Arsenal paid £2.5m for one of Palace’s strikers. The goals of Ian Wright and Mark Bright led Crystal Palace to third place at a time when only the first two teams in the First Division advanced to European competition; indeed, 1991/92 would be Liverpool’s first time in Europe after a six-year ban, as they finished seven points behind Arsenal.

In much the same way as Liverpool have been at Anfield, Arsenal were irrepressible at Highbury: 4-1 against Chelsea and Sheffield United 4-0 against Southampton and Crystal Palace, 3-0 wins against Liverpool and Derby County 3-0, a 5-0 against Aston Villa 5-0 and, on the last day of the season, a 6-1 destruction of Coventry City. ‘Go out and look like champions. Go out and be the Arsenal,’ Graham told his team who according to Adams was ‘probably the best Arsenal team I played for’.

David Seaman had already played for England while he was at QPR, travelling to Italy as third-choice keeper behind Peter Shilton and Chris Woods for the 1990 World Cup. In front of an elite defence, he was able to add some glittering medals to his shelf of caps, going on to become a cornerstone of Arsene Wenger’s first great Arsenal team. Highbury housed a ‘divine ponytail’ before Manu Petit.

The Bould-Adams partnership was well drilled and Dixon, Bould and Winterburn played every game, thus limiting David O’Leary to 11 starts. In 1947 the Arsenal had played 18 games before losing their invincibility; in 1990/91, it took 24. It was even more impressive because Arsenal’s captain was jailed for drink-driving, as he detailed in Addicted. Perhaps only when Eric Cantona was banned from playing in 1995 is there any direct precedent for a team’s key player to miss most of a season due to off-field indiscretion (with apologies to Rio Ferdinand and Carlos Tevez).

Weeks after the Old Trafford game, Manchester United came to Highbury for the Rumbelows Cup tie and scored six. Smith scored Arsenal’s pair but United dominated. Youtube highlights, with commentary from Clive Tyldesley, document a wonderful second-minute goal fired in from about 30 yards by Clayton Blackmore and an even better third goal from Lee Sharpe: ‘an absolute pearl’ with his right foot going in off the underside of the crossbar. He added two more and it was the only hat-trick conceded by the back four all season.

In his memoir, co-written with David Conn, Sharpe describes the night as the one he ‘hit the big time’, all the more because ‘football wasn’t all over the TV’. He reveals that Graham, who managed Sharpe when they were both at Leeds, ‘used to make his teams defend by trying to push his wingers inside all the time. He was paranoid about the opposition getting down the line and crossing it.’ United would play chess with Arsenal, ‘probing for when the defence would crack and leave an opening’. The victory, quite rightly, is claimed by Sharpe as ‘the beginning of a new era in English football’. Yet an Alan Smith hat-trick avenged the League Cup defeat to Manchester United (a 3-1 win), so the pendulum hadn’t fully swung yet.

The FA Cup semi-final was a North London derby held at Wembley Stadium. It is of course known for the Paul Gascoigne free-kick that Barry Davies memorialised with the words: ‘Is Gascoigne going to have a crack? He is, you know…’ Smith scored Arsenal’s consolation in a 3-1 win.

Those with long memories will know that Arsenal had required three replays to beat Leeds United in the fourth round. The original tie finished goalless, while the replay at Elland Road was 1-1 and the second replay at Highbury was also a 0-0 draw. Paul Merson’s goal, one of 16 he scored that season, sealed a win in the third replay.

If you meet any Arsenal fan who watched the Graham Era team, ask them whether they were at all four ties that year. Being Swedish, potential purchaser Daniel Ek might have followed it via newspapers. Perhaps we should ask Mr Ek how many goals Merse scored in the 1990/91 First Division season.

Merson himself was nicknamed ‘son of George’, writing in his book: ‘They reckoned I got away with murder…I was probably the most badly behaved player in the squad. For some reason, George took a shine to me.’ Despite his antics away from the pitch, with drinking, drugging and gambling as leisure pursuits, Merson still performed when it came to it.

I hope he cherishes his First Division winners’ medal and that he gets to hang out in a socially distanced manner with the back four, Safe Hands, Perry Groves and Alan Smith this spring to celebrate 30 years since the victory.

Never mind the teams of ’89, ’98 and ’04. Let us celebrate the Class of ’91.